When we woke the rain had stopped. Around us, the stream and campsite were still flooded, but the water only reached the tips of my boots when I went to collect sticks for a fire. Despite all the wood being soaked I managed to make Ayamin a lemon and sugar, and by just after midday the sun had begun to shine once more, drying out our tents.

While Ayamin and I hung a few of our clothes and blankets on the tent to dry we watched a gathering of refugee men disappear into the forest.

‘I wonder where they’re going?’ I said.

Ayamin turned to a kid who was carrying a load of sticks past our tent and asked him. When he was finished telling her she turned to me.

‘They’re searching for a way around.’

I nodded, a smile forming on my face.

‘Have they found anything?’ I asked the kid.

He seemed a little surprised at me speaking but told me they had just begun a few hours ago and he didn’t know.

As the boy disappeared, I turned to see Ayamin staring at me, a funny expression on her face.

‘What?’ I asked, folding a t-shirt on Winnie the Pooh’s nose.

‘Your Arabic is getting pretty good,’ she said.

‘What do you mean?’

‘Well, you managed to ask that kid if they’d found something without completely butchering the words.’

‘Wait what?’ I thought back, it hadn’t felt like I was speaking Arabic, ‘Are you sure?’

‘Positive,’ she laughed, ‘How do you think he understood you?’

While Ayamin disappeared back inside the tent, I stood frozen, still holding my shirt. I’m semi-good at a language, I thought. My eyebrows wrinkled a little and then slowly a smile slipped onto my face. Right through school I’d never excelled at much, my exam scores ranged from bad and very bad to did not attend because buying cigarettes was more important. Yet somehow, I’d managed to learn a language in just a few months.

The smile grew wider and… I felt proud.

We’d eaten the rest of the bread, and finished off the other half of a lemon when the men arrived back at camp. They moved as a group before dispersing into their tents.

I tried to ask what they’d found as they passed, but they just shook their heads. Standing next to me, Ayamin looked worried.

It was only the next night that we found out what was happening. We heard a tapping on the side of our tent, Ayamin unzipped the door, and in popped the head of the grandma whose site we’d helped build. In her hand, she held a small roll of campfire bread.

She handed it to Ayamin then beckoned her closer. The grandma whispered into Ayamin’s ear for a minute or two then looked at me, gave a wink, then disappeared from our tent.

Aya zipped up the door then leaned closed to me on the mattress, ‘So apparently they think you’re a North Macedonian spy.’

I frowned, ‘A spy? Why would I do that?’

She shrugged, ‘I don’t know…. You’re the spy, you tell me,’ I stared at Aya until she started laughing, ‘These people are just worried.’

‘So they won’t tell us how to get through?’

She shook her head, ‘Fortunately, you made friends with the right family, the grandma told me they’re leaving when dark falls tomorrow night.’

I grinned, ‘And we’ll just sneak along?’

‘Yep, we’ll just sneak along.’

****

You could feel the tension in the air the next morning. An outsider would think nothing of it, but the fact there was no laughter, no screaming said a lot. The camp was mute.

Ayamin and I packed up everything inside our half-dry tent and left the outside completely untouched. Occasionally I’d glance at the border guards. They didn’t seem to notice us.

None of the refugees spoke to me, but at the same time, no one told us not to come. In my mind that was about as good an invite as we were going to get.

As night approached, Ayamin and I were rearing to go. We sat in our tent talking about leaving the mud behind.

Darkness fell and we began to hear soft Arabic voices and the clinking of metal as tents were packed away.

Ayamin and I crawled from ours, dragging the backpack behind us. We had our poles folded up and pegs stashed away by the time the first families began to leave. Someone had judged the night perfectly, and there were only clouds in the sky, with no moon to light us up.

Ayamin and I stuffed the fabric of the tent into the pack, and I hoisted it onto my back – groaning just a little, ‘I don’t remember it being this heavy,’ I said.

Ayamin poked me in the shoulder, ‘You’ve just got lazy, that’s why.’

I reached for her, but she darted away, ‘See slowpoke?’

Then with white teeth grinning in the night, we made our way towards the forest.

The fallen tree over the stream sat in place, but it was hard to balance in the near-darkness. A woman in the family in front of us had a dim torch that they shone to help us cross.

‘Thank you,’ I said in Arabic. The man beside her smiled until the dull light showed my face, then he turned to the woman.

‘Turn around, let’s go,’ he said to her, before letting out an angry string of words that I didn’t ask Ayamin to translate for me.

‘I’m guessing he’s not my biggest fan.’ I whispered as I helped Ayamin over a branch that blocked the path.

We followed the pinpricks of light and the trail that another group had left, stumbling and falling over sticks and stumps and shrubs until we reached what was basically the entire population of the camp all gathered upon the riverbank.

Wary eyes turned to us and some people murmured a little to each other. I gazed at the river, pretending I didn’t see it

While latecomers continued to arrive, the camp watched two men tie a long rope around the waist of a fit-looking, sixteen-year-old guy.

When the rope was secured, an older man called out and everyone with a torch aimed it at the river. The rope guy took a series of breaths, then plunged into the fast-moving water.

His head broke through the surface and he began swimming long freestyle strokes towards the other shore. It wasn’t until he reached the middle that he began to drift downriver.

The men on our side continued letting out the rope until the teenager had washed up on the other bank. He was ten meters further downstream than where he’d started. As he hauled himself up, everyone around us gave a small cheer for him. Ayamin took my hand as the men on our side tied the rope onto a sturdy looking tree, ‘It’s going to be freezing.’ she whispered.

I nodded, ‘How about we just sneak into first class on a train?’

She grinned, ‘Champagne and decent food would be a hardship, but I guess it’s one we could bear.’

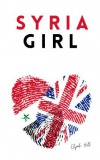

I stared up at the sky, she looked across the water, ‘One step closer to England,’ she whispered.

The guy who’d swum across ran up the riverbank until he was standing opposite us. He wrapped the rope around the base of a sturdy tree once, twice, three times then tied it off and gave the thumbs up.

Whole families with the kids riding on their parents’ shoulders began to slosh through the water. When the current caught them our fellow refugees clung to the rope that had been set up, using it to drag themselves across.

I spotted my campfire bread family down by the water and nudged Ayamin, ‘Come on, let’s go.’

We stood to our feet and moved to the water’s edge. The grandma was trying to organise everybody. One of her sons had to take his daughter across, but that only left one son for her husband in the wheelchair.

‘We’ll have to come back for you,’ she was saying. But then she heard our footsteps and the old woman stared at me as I came to a stop in front of her.

I smiled and nodded to her and that seemed to be enough.

‘England man take him,’ Grandma said, pushing her son to the other side of the wheelchair.

I looked from the grandfather to the son and nodded at each of them before the son and I hoisted his father, chair and all, onto our shoulders.

We sloshed into the water. And as it began to fill my boots, I let out a little yell of excitement. The cold had got my adrenaline flowing. I felt strangely alive.

By the time the son and I were reaching the middle we were finding it harder and harder to reach the bottom, the cold water came up to our chests and we began to drift downstream until we hit the rope. It dug into my side as I fought to get a foothold. The son slipped and disappeared under completely. The old man’s feet and knees dipped into the water.

I pushed a little further towards the other side before I too felt my head drop beneath the surface. Dark water swirled around me and my arms and shoulders were aching from carrying the grandad, I felt my knee hit rock and that made me kick out instinctively, my foot pushed against the sand and I shot back to the surface. The rope grazed my side as I leant into it. I found my next foothold, took a deep breath and pushed once more. This time I didn’t go under.

The son grinned at me and clung to the wheelchair. He was shivering like crazy, but the ground was beginning to slope upward. ‘Let’s go, let’s go!’ he whispered.

Behind us, Ayamin held the pack above her head as she emerged from beneath the water.

At the other side two men helped lift the grandfather from our shoulders, we climbed up onto the bank and I slapped hands with the son. Both of us grinned in the cold.

‘Well done,’ he said in Arabic, and I nodded, ‘To you too.’

The grandfather laughed, ‘I feel like a king.’

The two of us helped Ayamin get the pack up the bank. When she hugged me I could feel her relief. It wasn’t just making it across the river, we’d also left the dreaded field of mud behind.

We shoved on some dry clothes and our wet boots, then she took my hand again, ‘Time for the open road!’

One of the men took the lead, and we began walking along a small footpath that led away from the river. I helped the family out with their wheelchair a few times as dawn began to approach, and the grandma helped our stomachs with a snack of seeds.

By the time the sun was up, we’d met a road end. Family groups began to leave with spaces of five minutes between each one and soon Ayamin and I were walking alongside our new adopted family, with Grandma leading us from the front.

****

Our first days in North Macedonia were spent walking through its central valley. The ground was relatively lush and mountain ranges watched over us from a distance.

Progress was much slower travelling with the grandfather. His wheelchair was constantly getting stuck on roots and stones.

The hills were the worst though. Although he wasn’t much more than bones and clothing, Grandpa’s weight seemed to double every time a slope appeared.

One hill in particular took us nearly two hours to get over, and that was with me and the old man’s two sons taking turns to push.

At one point I was nearing the top. My breathing was ragged and I could feel my legs starting to ache.

‘I think last night’s apple potatoes have gone to your hips Grandpa,’ I wheezed.

‘Well, they must’ve gone to yours too boy. Look how slow you’re moving.’

I gave an out of breath chuckle and then heard a chugging from behind me. I turned back and watched as a train steamed by. The breeze it stirred up was wonderfully cooling and it gave me a good excuse to pause and catch my breath.

‘Damn I wish we were on that train,’ I said.

‘Damn I wish I had legs,’ Grandpa croaked, ‘But that ain’t happening any time soon.’

I stared at the train… at the wagons of logs moving past us… and then it was gone.

When we crested the hill, I spotted a small train station in the valley below us. The train we’d seen had stopped there, and that gave me an idea.

****

It was night when the train arrived. The slow clack of its wheels bouncing along the track was like a countdown timer. I peered both ways from our little hideout in the grass.

‘No one’s watching.’

The face of Mahdi, the eldest son, appeared beside me. A wild grin showed on his white teeth. ‘Let’s go then.’

He ran over to the open sided carriage that was just stopping in front of us. Hundreds of logs were stacked on it, but the steel beams that held them in place gave a narrow shelf to sit on.

Ayamin grabbed my hand and the two of us ran to join him while the grandfather was wheeled over by Mahdi’s younger brother.

On the other side of the rails was the dull sound of wood being dropped onto the train. They were filling up the bays fast.

The grandfather was pushed onto the carriage by his two sons, then they helped Grandma climb on. Just as the train gave a blow of its horn Ayamin and the rest of the family piled on. The kids scrambled up the railing like monkeys. I gazed both directions down the railway line, making sure we hadn’t been spotted before stepping onto the metal railing and climbing aboard.

‘Get back, get hidden,’ Mahdi whisper-shouted to us, ‘Someone’s checking the chains.’

We pressed our backs against the logs, and two of the children held their hands over their eyes. The rattling of chains was distant at first but got closer and closer. Chi-ching, chi-ching, chi-ching…

At the back of the train, someone began shouting in Macedonian.

The man who’d been rattling the chains shouted back and then broke into a jog. I held my breath as he passed us by, his eyes focussed on the end of the train.

We heard the two men talking and then some sort of decision must’ve been reached because the crunch of their footsteps moved back towards the station.

With a jerk, the train began to move off and next to me the family fell to their knees in prayer. Well, most of the family. The youngest was staring at me, he had these big brown eyes. Ayamin and I looked at each other, then back at those eyes full of worry and excitement.

‘I’ve never been on a train before,’ he said, ‘Do we get to see the conductor?’

The train’s horn blew. I took Ayamin’s hand and we leant back against the trunks of the beech trees. Their scent washed over us as our railway car left the yard and the cool night air began to make me shiver.

Ayamin reached for our bag, which sat between my knees, flipped the clips and pulled out our blanket, she wrapped it around the two of us. The train clattered on and on.

****

In hindsight it was amazing we lasted as long as we did. But at the time, being discovered by the train guards was like a cold slap of water in the face.

We’d left North Macedonia’s wall behind and passed through into Serbia… The sun came out, we passed through stations and countrysides and snacked on a bag of nuts Grandma had been saving.

Just after pulling out of our fifth loading yard, the crop fields whizzing past us began to slow. Within two minutes the train ground to a halt.

‘Repairs?’ I whispered.

‘Animal on the tracks,’ Ayamin suggested.

We heard the crunch of multiple boots on the gravel. They were moving quickly.

‘Don’t move,’ Grandma whispered, she clutched one of the children’s hands, ‘Be brave for me.’

The boots came to a stop, the guards stood there staring at us. There were three of them, they held batons in their hands and hate in their eyes.

One of them was sweating, had a tiny moustache, and seemed to be in charge. He shouted something in a language I couldn’t recognise and they advanced, batons drawn.

The first blow from one of the lackeys came swooshing down towards my head. I moved sideways and it caught my collarbone with a dull thud that left a patch of pain.

Two of the women screamed and we tried to back ourselves up but could go no further than the beech logs. I wrapped my arms around Ayamin and rolled so only my back was facing the guards. Their batons hit my ribs and smashed down on my spine.

I felt something crack and breathing became painful.

The kids, sheltered by their fathers, were bawling.

When the beating stopped, a hand grabbed my hair and used it to yank me from the train. The rocks tore into my hands as I hit the side of the railway.

Grandpa, sitting in his run-down wheelchair had clung to the logs right through the beating without making a sound. When the rest of us had been yanked from the train the guard with the tiny moustache climbed onto the carriage. He grappled with Grandpa until the old man was sitting right on the edge of the carriage.

The guard spat in Grandpa’s face.

‘Kol Khara,’ Grandpa said, Eat shit.

The man yelled, leapt forward and kicked the old man straight back off the train.

Grandpa’s spine landed with a thump on the sharp rocks of the train track, he let out a soul-destroying scream. I leapt up and tried to drag him and his wheelchair away.

But the guards were ready for that. The tallest one swung his baton and a dull thud hit my shoulder. My arm transformed into a river of pain but I clung to the wheelchair and dragged him back while Mahdi and Jamal pushed at the men.

The men yelled, spat on us, and then walked back towards the carriage slapping each other on the back. I still held Grandpa in my hands. He was crying and the tears mixed with blood from a cut on his cheek.

In that moment I snapped from self-preservation to anger. I’d landed not far from an old fencepost.

I grabbed it and ran towards the train which had already begun to move off. I tried to catch up to the men who’d beat us. You’re going to pay. I thought, You cowards.

But a sharp pain shot through my chest with every step. I was out of breath. I felt weak and the train was leaving me behind.

I turned on the passing carriages and whacked my stick against the train until it snapped on one of the wheels. I threw my stub at the final carriage and it bounced off with a small thud.

I shook my head as I fell to my bloody knees, sometimes in life, there is no justice.