Discord | Website | Twitch

I rubbed my leg and felt the bulged scars on my leg, small divots and patches and raised flesh tender across my calf. If the book was true then there were teeth here once interred deep. Now it was only man-leather for a whip driver. Then to my arm, my broken (now fractured) hand, where raising the sleeve of my white prisoner gown, across my arm were the burned sections across my forearm. Patches and patches of bald and of scars and of history written.

If the stories were true.

“Where did you all go after Lao-lo?” Ritcher asked.

“I don’t know.”

It sank deeper into me like a capsized ship, each memory landing at the floor of my consciousness.

“Then keep reading, Virgil. I didn’t tell you to stop.”

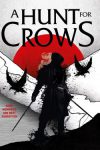

There was a child once who dreamed of being a hero. A child from another land who believed that there was more than the inanities of gluttony, who maybe could not voice it or even think it then but could feel it in him. A boy named Virgil who could not admit to being a crow but wanted, above all else, to be accepted as one.

“Are you listening?”

That boy was dead now and I was his replacement.

Rain poured against stone, filling every little gap and dripped from the cave top, rained walls made sticky with the grime and sweat and blood of all seven floors above in Shrieker’s Veil. It went down my face like tar, viscous and with running threads as I squished the water between my finger tips.

“Virgil?”

“Yeah. I’m listening.” I said. The book laid on my side, my arms wrapped around raised knees.

A past Virgil with secrets I’d lost, who knew more in his base and sad upraising than in my now five years in this realm. What did Virgil know? What did I come to learn all these times? Memories of the past; further beyond the journal.

That I’d gone to Australia after being kicked out of the house by my father. That I’d used my savings in some stow away bank before he could deplete them, that he wasn’t all too happy with my decision to quit business school. That I’d offered him an alternative, philosophy or perhaps literature and that he’d screamed at me with profanities. Father always wanted me to be like him. The business adept from Harvard.

So (or rather, So’s) at the time I left. Went to Australia for winter, meaning to forget. Held a few parties on the yacht, had done what I’d always done and wasted away in the company of strangers with diminutive worries in the back of my head. At least, I thought they were.

Then one day my boat was abducted and it sounds ridiculous, even now.

“Keep reading Virgil.” Ritcher slapped his chair.

“I think I’m done for now.” My eyes went to the corner of the cell. A rat raised its small snout up and looked at me with a sidelong glare. It scurried back in its hole.

What’d happened at the yacht? I rubbed my head like a genie beckoning wisdom from what little working gray matter I had. Well…I remembered, in the yacht, many years ago before Xyra…I remembered…I was shot in the head trying to escape pirates. What a stupid way to die, and I had died and now I was here.

It was all coincidence, wasn’t it? My death? My run with the flock? Ritcher?

Maybe. Or a kind of atomic fate so complex and invisible that I could not be aware of it, like every other man forced to walk earth, bound here to some thread unaware of its death grip, a thread swallowing all.

“Times not up yet, Virgil.”

“It is for me.” I said. “I know enough for one day. It’s starting to give me a headache.”

“I don’t care about your headache.”

“You will when I start losing my mind.” I threw a rock in between a crack in the cell, it danced across and echoed. “Do you think it comes like gentle sowing, one thimble turn at a time? One image on the quilt stitched slowly? No. It comes all at once. It’s a sudden drape, a throwing into deep end. All my memories are flooding me right now. And I don’t know how to handle it, I don’t even think I should handle it. I just want some rest, that’s it.”

His tongue rolled inside his mouth. I saw the veins on his neck, in his hand, work themselves back into fat muscles.

“Alright.” He said. “Have it your way. But we’re talking tomorrow.”

And hopefully it would be the last time we spoke. If Chaucer was right, at least.

“Tell them I’m not working tomorrow.” I said.

Ritcher’s eyes narrowed. His brow furred. He looked down and nodded.

Out on the range, pressed up against the waves and crash of water the shadowy figures work with relentless strain. None of them with half the courage to turn the picks around at their whip bearers. None of them courageous enough to jump. They mine the stones and sift the salt and volcanic glass and look for the shine of saphire somewhere in the rubble. Their black fingers working, dragging across the screen for gems.

It wasn’t as if these were even valuable, I’d like to believe they weren’t. That it was all just work to keep the prisoners preoccupied. Something to ease the boredom of the guards, because I’m sure torture and I’m sure fishing becomes a bore if you do it long enough.

I stood afar, someways pays the palm trees and the low fields of dry grass. Not inside the Veil, though I was supposed to be. I stood outside in what was the tool shed and the shifty guard at the door counted his coins and whistled. He went some paces and away he went from the shed. I walked back some and sat on an anvil. I put my feet up against the funnel of a furnace. Chaucer held a lizard with a pinched finger. The old tall brute of a companion stood by his side, his own black lizard in his hand. They both let it go. Chaucer won. Claps and moans were heard across; it sounded more than the four that were actually hear.

We sat around some and after a while took to drinking. I didn’t even have to smuggle the bottles. Chaucer had them all here.

“Why’d you ask me to ask Ritcher for wine if you had some?” I asked.

“So you could get used to asking him for stuff.” He popped the cork with his mouth.

“You should go through the plan again.” I rested my head on my palm. The tall man, the dwarf and Chaucer looked out the window.

“Why? You gonna forget that too?” He asked.

“I might.”

“You know the plan. I don’t want to repeat it, it might hex it.” He said. “All you need to know is that we’ll all be out as soon as those ships roll on by.”

“Is that right?” Their figures were dark in the shadows of the shed, long stilted hammers and rakes and hoes and pick axes lined the walls. There was no need for us to take them, these weapons. There was no point to any of it now. I watched their faces hidden behind the row of shadows, the blackened cells that cut their visage in quarters.

It reminded me of old friends.

“What are you going to do when you get out?” I looked down at my cup. Hope had come for me, I hated that. Vulnerability.

“I’m going to go to the shores of Loshka. I’m going to the whore house and rounding up as many mates as I can.” He poured heavenberry wine down into the wooden cup. “Then I’m going to go kill my father.”

No words were spoken between us. I saw nothing but his face staring down the purple gleam, a waterfall of royal blood that came down into the cracked rimmed wood cup.

“What about you?” He asked.

“I’ll probably read a little.” I said. “See who got me here.”

“Then?”

“Then I’ll deal with it.” I said.

“Are you going to kill the man who sent you here?” He asked. “Who got you trapped?”

“Sometimes.” I breathed heavy. “Sometimes I wonder if I actually deserved to be here. If I tried to kill the king, if any of that is true.”

“And what if you did?”

“Maybe I'd subject myself to rot then. Maybe I wouldn’t be able to tolerate being a bad person. Not that I think I'm bad.”

“So, then, do you think you’re a good person?” Chaucer smiled.

I looked down at my wrapped hand, the bones barely back in place and still aching and bruised behind the white stained threads.

“I think there are limits to evil and I’d like to think I’m behind that limit rather than over it, is all.” I said. “I’ve wasted enough life on guilt, I just want some peace is all. Maybe find a shack somewhere in the corners of Xyra.”

“Go to Shalos.” He said. “There’s beautiful beaches and beautiful women.”

“I think I’ve had enough of the ocean.” I drank. “And the beaches. Fuck the beaches.”

Chaucer raised his cup. “Fuck the beaches.”

We all did and tapped away at our mugs. No other words were spoken that day, we maintained our silence in the darkness, our eyes unsteady under the effects of the wine.

Tomorrow it’d all go through. Tomorrow.

I wish I wasn’t hoping, but if I had to admit to something, then it was that there was a fire in me that could not be extinguished. I could not stomp it out, I felt it in my chest.

I wanted to walk on the mainland. I wanted to take a free step out.

I hated wanting and hope and expectation.